It's an interesting topic given some of our previous inquiries regarding puppoetics. Karagoz is the lead character in almost all of the scenarios of Turkish shadow puppet theater. A parallel in Lao culture would be shadow puppet stories from Kalaket and Manola and Sithong, or episodes of Xieng Mieng or Phra Lak Phra Lam.

Soganci insisted that schools and art "can still play essential roles in facilitating students to better understandings of human cultures through a historical perspective." (Soganci, 34) He was further curious about the way students could be shown inferior reproductions of classic images and characters from a culture's traditions to examine what the quality of mass-media images can have and their effects on us.

Soganci lamented that "philsophical richness is considered irrelevant" in popular media. He noted that in the past, in Turkish shadow puppetry, the white screen symbolized temporary life, while the puppets were humans with almost no will, and the unseen puppeteer represented a superior will manipulating everything. The light was considered the energy that enables us to see the world while concealing the Divine. This was a scenario that had significant relationship to Islamic philosophy, even as the art form emerged from techniques learned in Asia. (Soganci, 35-37).

By the final summation, Soganci suggested that we ought to explore what schools could do to "re-attach the detached by critically unfolding the ways popular media exploits examples of visual culture. While not all images in popular culture exhibit a detachment of images from their cultural, historical, and artistic essences, it should still be considered one of the art teacher's essential duties to keep a close and critical eye on mass media." (Soganci, 38)

For those of us engaged in both visual and literary Lao American arts, these are questions and opportunities applicable to our own experiences that we ought to consider.

As poets and writers, I would not want to see us shy away from engaging with the art and techniques of our past, but I think it's important to study the philosophies and aesthetics underpinning the particular techniques and meanings. We should also still seek ways to innovate and continue to expand our artistic vocabulary. The final words have not been written. There's so much we can yet explore.

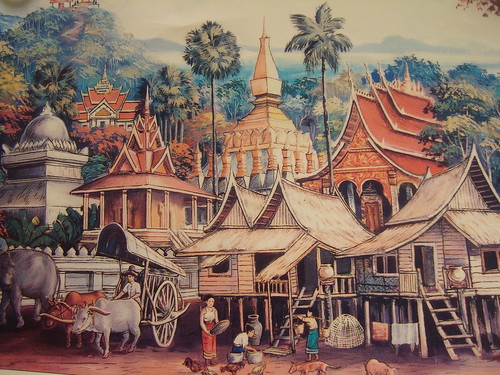

Lao art has historically been far more liberal in the diversity of forms it has taken. There are certain guidelines and expectations, but the final executions are more often than not distinctive to particular artists in a given generation than not, as we see in the wide range of Buddhas from Laos. This would apply not only to our visual arts but also our literature.

This is still a difficult proposition in the US given the struggle to maintain and effectively support arts education in the schools from a mainstream perspective. Among Lao American programs, most are struggling to teach the traditional forms and baseline principles that we do not regularly get a chance to examine more ambitious approaches for integration into our curriculum. We should consider what can be done to reduce those barriers.

No comments:

Post a Comment