Honored to announce that I'll be the 2016 guest speaker at the Year-End Ceremony for the USEAA (United Southeast Asian American) Program at Fresno City College in May! This year marks the 17th year of serving students from Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and other parts of Southeast Asia, including many from refugee backgrounds.

I've been a long-time advocate for their program and the work they do to expand opportunities for Southeast Asian American youth who are often the first in their families to attend college.

I applaud their journey and look forward to speaking with them soon.

Poetry, science fiction, fantasy, horror, and culture from a Lao American perspective.

Thursday, March 31, 2016

Sunday, March 27, 2016

Friday, March 25, 2016

Haiku Movie Review: Batman vs. Superman

"Heroes" slug it out,

Wonder Woman steals show.

But that was not hard.

Wonder Woman steals show.

But that was not hard.

Thursday, March 24, 2016

Crossing Borders: Hearing other Voices in Poetry 2016 Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets Spring Conference

I'm honored to announce that I, Kao Kalia Yang, Timothy Yu and Ed Bok Lee have been selected as featured poet-presenters at the Spring Conference 2016 of the Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets at the end of April.

The theme of this year's conference is "Crossing Borders: Hearing other Voices in Poetry." A big thank you to my fellow poet James P. Roberts for helping to arrange this amazing undertaking. The event begins on April 29th at the Crowne Plaza in Madison, Wisconsin and continues until April 30th. What a wonderful way to close National Poetry Month and head into Asian Pacific American History Month.

A semi-annual event, it typically gathers between eighty to a hundered of the state's most passionate poets gather to engage in workshops, readings, open mics, book fairs and a banquet/awards ceremony. Among the events scheduled this year is an Open Mic Poetry session done in a round-robin style, emceed by F. J. Bergmann. All experience levels are welcome.

Established in 1950, the Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets (WFOP) is a non-profit organized around poetry: reading poetry, writing poetry, and advocating poetry. The organization was created exclusively for literary purposes with the hope that Wisconsin could become more poetry aware and appreciative of its poets and poetic heritage.

I'll be reading a selection of new and classic poems of mine from my collections DEMONSTRA, Tanon Sai Jai, and of course, On The Other Side Of The Eye as I mark 10 years of this blog this year, and the 40th anniversary of the Lao diaspora.

Timothy Yu is associate professor of English and Asian American Studies and director of the Asian American Studies program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of Race and the Avant-Garde: Experimental and Asian Poetry since 1965 (Stanford University Press), which won the Book Award in Literary Studies from the Association for Asian American Studies. He is the editor of the collection Nests and Strangers: On Asian American Women Poets (Kelsey Street Press), and he also serves as an editor of the journal Contemporary Literature. His latest book is a poetry collection, 100 Chinese Silences.

Kao Kalia Yang is a Hmong American writer and author of The Late Homecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir from Coffee House Press. Her work has appeared in Paj Ntaub Voice Hmong literary journal and numerous other publications. She wrote the lyric documentary, The Place Where We Were Born. Her new book, titled The Song Poet, will be published in 2016 by Metropolitan Books.

Ed Bok Lee is an American writer. His most recent book, Whorled (Coffee House Press), won the 2012 American Book Award, and the 2012 Minnesota Book Award in Poetry. His first book, Real Karaoke People (New Rivers Press), won the 2008 PEN/Open Book Award, and the 2008 Asian American Literary Award (Members’ Choice Award).

You can learn more about the event at www.wfop.org. Members can attend for $50, which includes meals. Non-members can attend for $80. Special rates for first-timers and students are available.

The theme of this year's conference is "Crossing Borders: Hearing other Voices in Poetry." A big thank you to my fellow poet James P. Roberts for helping to arrange this amazing undertaking. The event begins on April 29th at the Crowne Plaza in Madison, Wisconsin and continues until April 30th. What a wonderful way to close National Poetry Month and head into Asian Pacific American History Month.

A semi-annual event, it typically gathers between eighty to a hundered of the state's most passionate poets gather to engage in workshops, readings, open mics, book fairs and a banquet/awards ceremony. Among the events scheduled this year is an Open Mic Poetry session done in a round-robin style, emceed by F. J. Bergmann. All experience levels are welcome.

Established in 1950, the Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets (WFOP) is a non-profit organized around poetry: reading poetry, writing poetry, and advocating poetry. The organization was created exclusively for literary purposes with the hope that Wisconsin could become more poetry aware and appreciative of its poets and poetic heritage.

I'll be reading a selection of new and classic poems of mine from my collections DEMONSTRA, Tanon Sai Jai, and of course, On The Other Side Of The Eye as I mark 10 years of this blog this year, and the 40th anniversary of the Lao diaspora.

Timothy Yu is associate professor of English and Asian American Studies and director of the Asian American Studies program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of Race and the Avant-Garde: Experimental and Asian Poetry since 1965 (Stanford University Press), which won the Book Award in Literary Studies from the Association for Asian American Studies. He is the editor of the collection Nests and Strangers: On Asian American Women Poets (Kelsey Street Press), and he also serves as an editor of the journal Contemporary Literature. His latest book is a poetry collection, 100 Chinese Silences.

Kao Kalia Yang is a Hmong American writer and author of The Late Homecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir from Coffee House Press. Her work has appeared in Paj Ntaub Voice Hmong literary journal and numerous other publications. She wrote the lyric documentary, The Place Where We Were Born. Her new book, titled The Song Poet, will be published in 2016 by Metropolitan Books.

Ed Bok Lee is an American writer. His most recent book, Whorled (Coffee House Press), won the 2012 American Book Award, and the 2012 Minnesota Book Award in Poetry. His first book, Real Karaoke People (New Rivers Press), won the 2008 PEN/Open Book Award, and the 2008 Asian American Literary Award (Members’ Choice Award).

You can learn more about the event at www.wfop.org. Members can attend for $50, which includes meals. Non-members can attend for $80. Special rates for first-timers and students are available.

Pushing Margins with Hmong American Writers Circle!

The Hmong American Writers’ Circle is proud to present “Pushing the Margins” , a 2016 AWP off-site reading in the Mark Taper Auditorium at the Los Angeles Public Library (630 W. 5th Street, Los Angeles, CA) on Thursday, March 31, 2016 from 6:00pm to 7:30pm.

On that night, HAWC continues to push itself and the work of HAWC beyond the margins by also celebrating the recent accomplishment of Mai Der Vang, winner of the 2016 Walt Whitman Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets. A special thank you has been extended to their friend and ally Alex Espinoza for helping them to secure the venue.

Members of the Hmong American Writers’ Circle will be reading from their bodies of literary work. With Hmong-American literature nearly non-existent in the Asian American literary canon, let alone the national landscape, HAWC continues to push forward in creating accessible spaces for Hmong American writers to share their work with the public. Readers include Burlee Vang, Mai Der Vang, Soul Vang, Andre Yang, Ying Thao, and Anthony Cody.

Founded in 2004, the Hmong American Writers’ Circle organizes literary workshops to foster creative writing in the Hmong community and in the California Central Valley. Hmong-American literature is nearly non-existent in the Asian American literary canon, let alone the national landscape. With the knowledge that no definitive accounts of Hmong literature exists, many Hmong writers often write from a place of absence while struggling to create literary traditions in a culture that could face extinction.

About the readers:

Burlee Vang (Founder) is the author of the chapbook Incantation for Rebirth (Swan Scythe Press, 2010). His prose and poetry have appeared in Ploughshares, North American Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Massachusetts Review, Runes: A Review of Poetry, among other publications. His work has also been anthologized in Twentysomething Essays by Twentysomething Writers: Best New Voices of 2006 (Random House) and Highway 99: A Literary Journey Through California’s Great Central Valley (Heyday). In 2006, he was the recipient of the Paj Ntaub Voice Prize in Poetry. He holds an MFA in fiction from California State University – Fresno, and is the founder of HAWC. In 2011, he, along with his brother Abel, were awarded a Nicholl Fellowship in screenwriting from The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He lives in Los Angeles with his wife, Mary, and their two children, Belle and Jude.

Mai Der Vang is the 2016 Walt Whitman Poetry prize winner, selected by Carolyn Forche. Her book "Afterland" will be published by Graywolf Press in April 2017. Her poetry has appeared in Ninth Letter, The Journal, The Cincinnati Review, The Missouri Review Online, Radar, Asian American Literary Review, The Collagist, and elsewhere. Her essays have been published in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the San Francisco Chronicle, among other outlets. As an editorial member of the Hmong American Writers' Circle, she is co-editor of How Do I Begin: A Hmong American Literary Anthology. Mai Der has received residencies from Hedgebrook and is a Kundiman fellow. She earned her MFA in Poetry from Columbia University. To read more about Mai Der, please visit her website: www.maidervang.com.

Anthony Cody was born in Fresno, California with roots in both the Dust Bowl and Bracero Program. A graduate of CSU-Fresno and a 2012 CantoMundo Fellow, Anthony has been writing poetry since first unraveling a poem in Spanish. His work has been performed in community theatre productions in California and NYC, and published in Juan Felipe Herrera’s 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border: Undocuments 1971–2007 (City Lights) and How Do I Begin?: A Hmong American Literary Anthology (Heyday), in which he was also co-editor, as well as a featured poet via the online site ToeGood Poetry. New work is forthcoming from Prairie Schooner. After serving as Managing Director of Arts and Culture at El Taller Latino Americano in NYC, Anthony returned to Fresno to work as Communications Manager for Fresno State's Theatre Arts program. To read more about Anthony Cody, please visit his website: www.anthonycody.com.

Ying Thao has a Bachelor’s of Science in Business Administration from the University of California, Riverside and a Certificate in Asian American Studies from California State University, Long Beach. He first connected Creative Non-Fiction through his participation in the HAWC workshop. As a gay Hmong American, Ying believes that his voice is rooted in the issues of both a gay male and a Hmong male, as these identities are seemingly diametrically opposed to one another culturally and socially. He hopes that through Creative Non-Fiction he can explore and find balance within the duality.

Andre Yang lives in Fresno, California. He is a founding member of the Hmong American Writers’ Circle (HAWC), where he actively conducts and participates in public writing workshops. He received his MFA degree from Fresno State where he was a Provost Scholar and a Philip Levine Scholar. There, he divides his time between teaching freshman composition and poetry. Andre is a Kundiman Asian American Poetry Fellow and has attended to the Tin House Summer Writers Workshop, the Napa Valley Writers’ Conference, and the UCross Foundation residency. His poetry has appeared in Paj Ntaub Voice, Hyphen Magazine, Kweli: Journal, the chapbook anthology Here is a Pen (Achiote Press), and the anthology Poetry of Resistance: Voices for Social Justice (University of Arizona Press).

Official National Lao American Writers Summit poster revealed

It's coming up fast on May 27-28th in San Francisco!

The Thao Worra Test on artificial intelligence

In light of the recent incident with the Tay A.I. chatbot that Microsoft tried to deploy that went pro-Hitler in less than 24 hours, I hereby proclaim this the Thao Worra Test. How long can your AI interact with humans and NOT turn "evil". I know. Some might say this isn't as important as the Turing Test or the Voight-Kampff test, but indulge me.

Considering defamation and invasion of privacy in Southeast Asian American literature

Earlier this year, Writers Digest had a nice post from US-based attorney Amy Cook about defamation and invasion of privacy in memoirs and non-fiction books. It's interesting reading, as applied to books published in the US. International law may have additional restrictions to consider, such as one nation with the lèse-majesté law still prominently on the books in Southeast Asia.

For Southeast Asian American communities beginning to develop more memoirs and non-fiction books about their experiences, emerging writers absolutely need to familiarize themselves with the limits of the law and where they have protected liberties.

Often, as we interact with several different cultures, both back in Southeast Asia and in the US, our perspectives can result in conflicting histories that differ from the current records of note.When we begin talking about details of the Secret War, the Killing Fields, and similar issues the matter can get extremely contentious.

This doesn't mean you can't write about them, but you need to do your research at many levels. In the Vietnamese community in the US, for example, accusations of communist ties or insinuating that women are prostitutes or whores has often been a dog whistle to chip away at different community members' standing. A recent case between two newspapers in California, however, illustrates the expenses and social consequences that can incur.

For Southeast Asian American fantasy, science fiction, and horror writers, if you're writing stories spinging off of our traditions and culture, you'll still need to be aware of these issues. Situations such as writing about alternate history, for example, can get complicated. What happens when the line between fiction and fact get blurred?

Over time, it's probable we'll see many more cases emerge that lead to some very heated disputes. Even as I encourage you to write to the limits of your imagination, you will also need to keep mindful of your footing.

For Southeast Asian American communities beginning to develop more memoirs and non-fiction books about their experiences, emerging writers absolutely need to familiarize themselves with the limits of the law and where they have protected liberties.

Often, as we interact with several different cultures, both back in Southeast Asia and in the US, our perspectives can result in conflicting histories that differ from the current records of note.When we begin talking about details of the Secret War, the Killing Fields, and similar issues the matter can get extremely contentious.

This doesn't mean you can't write about them, but you need to do your research at many levels. In the Vietnamese community in the US, for example, accusations of communist ties or insinuating that women are prostitutes or whores has often been a dog whistle to chip away at different community members' standing. A recent case between two newspapers in California, however, illustrates the expenses and social consequences that can incur.

For Southeast Asian American fantasy, science fiction, and horror writers, if you're writing stories spinging off of our traditions and culture, you'll still need to be aware of these issues. Situations such as writing about alternate history, for example, can get complicated. What happens when the line between fiction and fact get blurred?

Over time, it's probable we'll see many more cases emerge that lead to some very heated disputes. Even as I encourage you to write to the limits of your imagination, you will also need to keep mindful of your footing.

Wednesday, March 23, 2016

Silicon Valley Comic Con 2016: After Action Report

Sahtu Press survived the inaugural Silicon Valley Comic Con in San Jose! A big thanks to all of our friends and family who came to support us throughout the weekend. Held on March 18–20, 2016 at San Jose's McEnery Convention Center, it was a positive and promising event. I'm definitely looking forward to future events organized in San Jose.

We didn't have a chance to meet Steve Wozniak in person, but thanks to Madame Tussaud's we got the next best thing, at least.

There were some really creative visions participating this year, and the volunteers were all very helpful and attentive. There were some amazing cosplayers, of course, including Princess Mononoke!

Our panel went smoothly, with a good attendance for the panel considering that Steve Wozniak was speaking at the same time on the other side of the hall.Our thanks to everyone who came to hear about the history and trajectory of Southeast Asian American characters in the comics and what we're trying to do in our own work.

During our panel, we covered epic heroes such as Sinxay and the Ramayana, as well as more modern figures such as the assassin Cheshire Cat, Kevin Kho the One Man Army Corps, and the vigilante Kulap Vilaysack, aka Katharsis from The Movement.

Of course, in any such conversation, the subject of ghosts and the supernatural also came up, and we went over some of the legendary phi of Southeast Asian tradition, and where we might see some interesting writing in that regard. We're very far from seeing the final words on the subject.

Among the professionals I had a chance to meet that I most appreciated was Dan Brereton, whose Giantkiller series was one of my favorites in the 1990s. I've often demonstrated his work to my students as an example of how one develops a distinctive but versatile style professionally. You can always recognize his work when you see it.

I found it comparably easy to find parking and to make our way around San Jose during Silicon Valley Comic Con, and if they can maintain this level of quality and a good diversity of experts and emerging voices in the industry, I would definitely recommend it to anyone in the Bay Area. The next SVCC is scheduled for April 21-23rd.

We didn't have a chance to meet Steve Wozniak in person, but thanks to Madame Tussaud's we got the next best thing, at least.

There were some really creative visions participating this year, and the volunteers were all very helpful and attentive. There were some amazing cosplayers, of course, including Princess Mononoke!

During SVCC, Nor Sanavongsay and I were able to meet with both established and emerging artists, keeping a particular eye out for Laotian Americans. We spotted at least one in Artist Alley who'd come all of the way from Stockton, California. We were hoping to see our Lao American artist colleague, Samouro Baccam, but he couldn't make it that weekend.

During our panel, we covered epic heroes such as Sinxay and the Ramayana, as well as more modern figures such as the assassin Cheshire Cat, Kevin Kho the One Man Army Corps, and the vigilante Kulap Vilaysack, aka Katharsis from The Movement.

Of course, in any such conversation, the subject of ghosts and the supernatural also came up, and we went over some of the legendary phi of Southeast Asian tradition, and where we might see some interesting writing in that regard. We're very far from seeing the final words on the subject.

It was always interesting to see how different communities addressed some of the more famous characters from Marvel and DC. For instance, I spotted at least one Captain Mexico and the Mexican Punisher.

I found it comparably easy to find parking and to make our way around San Jose during Silicon Valley Comic Con, and if they can maintain this level of quality and a good diversity of experts and emerging voices in the industry, I would definitely recommend it to anyone in the Bay Area. The next SVCC is scheduled for April 21-23rd.

Mai Der Vang announced as 2016 Walt Whitman Award Recipient

A VERY BIG congratulations to Mai Der Vang who was selected as the 2016 Walt Whitman Award recipient by the Academy of American Poets.

This marks a historic precedent for the Hmong community, and I look forward to seeing her book when it comes out from Graywolf Press next year!

This marks a historic precedent for the Hmong community, and I look forward to seeing her book when it comes out from Graywolf Press next year!

Happy birthday, Akira Kurosawa!

Legendary film director Akira Kurosawa was born on March 23, 1910 and went on to create a deeply influential body of cinematic work before his passing on September 6, 1998. Some of my favorite works of his include Dreams, Rashomon, Kagemusha, Yojimbo, Throne of Blood, the Hidden Fortress, and The Seven Samurai. Be sure to watch one of them today. Each film is a tremendous exploration of human character and detail.

Angels of the Meanwhile coming April 1st

Just in time for National Poetry Month, my poem, "Thread Between Stone" will be part of the upcoming benefit e-chapbook "Angels of the Meanwhile," edited by Alexandra Erin. It's expected for a release on April 1st, and will help to defray medical costs and other expenses for speculative poet Pope Lizbet, who was injured in a car accident last year.

I'm glad to see so many in our community rallying together to support a fellow poet in their time of need. Many other talented writers have generously donated their work, including Catherynne M. Valente, Lev Mirov, Bogi Takacs, Christina Sng, Sonya Taafe, Rose Lemberg, Amal El-Mohtar, and Jennifer Crow. The cover art is by Amanda Sharpe.

Readers can learn more about this at: http://www.angelsofthemeanwhile.com

I'm glad to see so many in our community rallying together to support a fellow poet in their time of need. Many other talented writers have generously donated their work, including Catherynne M. Valente, Lev Mirov, Bogi Takacs, Christina Sng, Sonya Taafe, Rose Lemberg, Amal El-Mohtar, and Jennifer Crow. The cover art is by Amanda Sharpe.

Readers can learn more about this at: http://www.angelsofthemeanwhile.com

Monday, March 21, 2016

Kalounna in Frogtown marks 30 years

For an interesting "Where are they now?" question: 2016 is the 30th anniversary since the painting "Kalounna in Frogtown" was completed by Jamie Wyeth in 1986. It's currently on display at theTerra Museum of American Art, Chicago, Illinois. Jamie Wyeth is the son of the famed painter Andrew Wyeth. It's one of the first pieces of visual art by a prominent American artist I know of following te arrival of Laotian refugees. I don't think it's the Frogtown of St. Paul, however, so that leads to an interesting question of where did they meet?

Sunday, March 20, 2016

Friday, March 18, 2016

Hmong folklore recommendations

One of the topics I frequently encourage emerging writers to engage with are cultural folklore traditions. This includes myths, legends, folklore, anecdotes, and so on. In the Hmong community, I don’t think the last word has been written on this by far.

I hope we’ll see more works in the traditional and the experimental vein continue to emerge from this generation of writers. It’s especially important to try and document as many of the stories of the elders they have before that generation is lost.

Due to the historically oral nature of the Hmong community, many traditional stories and their variations are still unwritten. For those who are working with the Hmong community in their fiction, poetry, music and non-fiction it may be handy for you to have a solid baseline of Hmong folklore, legends and beliefs.

For my Khmu, Tai Dam, Lue, Iu Mien and Akha readers, I would certainly encourage you to obtain copies of these books in order to see if there are shared stories and to see how others with ties to Laos have made efforts to preserve their history. Four books that continue to be essential to me in my process since I first began research in the 1990s follow:

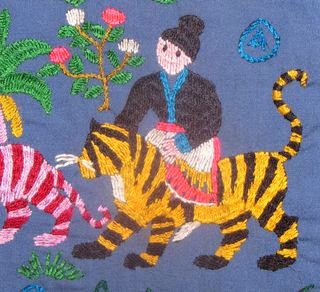

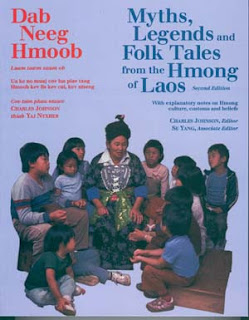

Charles Johnson and Se Yang worked very hard together to produce Dab Neeg Hmoob: Myths, Legends and Folk Tales from the Hmong of Laos. One might easily mistake it for a phone book at first at 520 pages. This is a bilingual text. It’s fair to say the 1992 edition’s illustrations and the typesetting definitely make it feel dated today. The organization of the copious notes can sometimes feel like a chore to wade through because they’re VERY comprehensive, although rarely repetitious, to their credit. It can be difficult to tell where one story begins, and another ends. But one should absolutely not let that deter them from using this book as a starting point reference. Likely more of our knowledge on Hmong beliefs and traditions have since been expanded upon in other texts, so keep that in mind that this is more of a snapshot of what was readily documented in the 1980s and early 90s. Some of the older beliefs have likely been forgotten or less well-known by the current generation. But the book definitely makes for fascinating reading. Take care of your copy if you can get ahold of one.

Hmong Art: Tradition and Change came out in 1986 from the John Michael Kohler Art Center in Wisconsin, originally tied in to an exhibit they’d had during the early years of the Hmong resettlement. There are some really amazing examples of Hmong traditional textiles, jewelry, musical instruments, weapons, and everyday objects from Hmong life with plenty of photos, a great history (for the time) and explanatory notes. While not strictly a book of folklore, the captions frequently mention the meaning of many of the objects and patterns we saw on Hmong objects of the 1980s, and I’ve found it valuable to refer to as we look at changes in the community 30 years later.

Grandmother's Path, Grandfather's Way (Poj Rhawv Kab Yawg Rhawv Kev): Oral Lore, Generation to Generation by Dr. Lue Vang and Judy Lewis is approximately 190 pages with very 1990s production values and somewhat simple illustrations and diagrams, but I consider it very important for its clarity on several folkloric beliefs including Hmong geomancy, textile symbolism, the paj lus (flower words) and other customs that typically aren’t included in discussions of Hmong culture. It went out of print without plans to reprint it, the last time I checked, so finding a copy may be a somewhat difficult process, but I wouldn’t let the price or the production values deter you considering the knowledge it contains. It’s not the last word on the subject, but there are notes you won’t find many other places yet.

Dr. Dia Cha holds the distinction of being the first Hmong woman to hold a doctorate in anthropology. And while I’ve been waiting for some time for her to complete her book on Hmong ghost stories, in the meantime, her collections on folktales of the Hmong remain standout classics. Folktales of the Hmong with Dr. Norma J. Livo is very well organized and clearly written, although it doesn’t go into as many in-depth details as Dab Neeg Hmoob. But it’s also one of the only ones on this list that remains relatively easy to find. It has reasonable depth and breadth, leading the careful reader to many interesting lines of inquiry in the future.

As a reminder, this isn’t an encylcopedic list, but simply four books I found very helpful for my work, and it may be helpful for you, as well.

Southeast Asian Youth Education and Career Conference: April 16th, 2015!

Each year, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee Area Technical College, Milwaukee Public Schools, Marquette University, University of Wisconsin-Parkside, Mount Mary College, and several community-based organizations work collaboratively to organize the Southeast Asian Youth Education and Career Conference.

The 2015 conference will be held on April 16th, 2015 at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The theme for this year’s conference is “Inventing Yourself: College and Beyond.”

The conference provides opportunities for Southeast Asian-American high school students to explore education and career opportunities, to interact with professionals from Wisconsin colleges and universities and other professions.

The conference also brings dynamic keynote speakers and presenters, who can serve as role models in their respective profession for Southeast Asian-American youths.

The conference’s aim is to increase the high school retention and graduation rates for Southeast Asian-American students and the skilled workforce of Southeast Asian-Americans in the Milwaukee area by encouraging them to obtain their post-secondary education.

Past conferences had attracted a great deal of interests from high school students and administrators, and we are expecting more than 300 students for this year’s conference.

The 2015 conference will be held on April 16th, 2015 at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The theme for this year’s conference is “Inventing Yourself: College and Beyond.”

The conference provides opportunities for Southeast Asian-American high school students to explore education and career opportunities, to interact with professionals from Wisconsin colleges and universities and other professions.

The conference also brings dynamic keynote speakers and presenters, who can serve as role models in their respective profession for Southeast Asian-American youths.

The conference’s aim is to increase the high school retention and graduation rates for Southeast Asian-American students and the skilled workforce of Southeast Asian-Americans in the Milwaukee area by encouraging them to obtain their post-secondary education.

Past conferences had attracted a great deal of interests from high school students and administrators, and we are expecting more than 300 students for this year’s conference.

Wednesday, March 16, 2016

Presentation notes: Transitions: Refugee Memories & Imagination in Diasporic Expression

Presentation Notes from UC Davis, March 7th, 2558

Preface: As a poet and a long-time presenter on various subjects involving Southeast Asian refugee literature in diaspora, I prefer my talks with my students to be conversational and organic rather than firm and fixed lectures.

Memory is a very funny thing, and I found recording what I talk about loses much of what I try to convey. I think poetry is best discussed in a certain 4-dimensional space that a camera from a fixed point or two rarely succeeds in capturing. So, I typically discourage recording for a number of reasons, including the challenge of creating a safe space for open dialogue on what are often sensitive issues. If a poet’s doing their job, then the best will stick and linger with you. Rarely the whole lecture. But something. And that’s an important part of our process.

Still, there are some things I like to consistently touch on. So, for those who couldn’t stay the whole evening, here are the notes I was working from. Those who were there will be able to tell you these were heavily adjusted on the fly to meet many of your questions. These might be helpful to you as you take your own literary journeys.

George Orwell, the author of the dystopian classic 1984 used to say that “A poetry reading is a grisly thing.” And I’ve been to enough in my lifetime that I can see where one might get that impression. A good poet tries not to leave the room with more, newer enemies of literature than when they first walked into it. I think that should be our professional courtesy to each other.

But why poetry? I think poetry is a form that’s mystifying to many people because of the way it is typically introduced to people in the early years. We’re used to forms of literature and language where written things spell everything out precisely and clearly. It’s a very modern American thing to love the simple and the practical and the obvious when it comes to using everyday language.

The physicist Paul Dirac used to joke, semi-seriously that “"In science one tries to tell people, in such a way as to be understood by everyone, something that no one ever knew before. But in poetry, it's the exact opposite." I think about that a lot as I create my own poems, as I think back to the transitions, the journeys that have led me to this path as a poet.

As a Lao American poet, my particular focus is on speculative poetry, a branch of poetics that embraces the fantastic, the imaginative, the mythological, the supernatural and the unreal. It’s an area where I presently seem to have little company, yet it’s a realm of significant and vital importance for refugees in our reconstruction, as I hope to explain throughout the remainder of this conversation tonight.

The Vietnamese poet Mong Lan used to say that all poetry is love poetry, and to a degree I agree with her. But love, true love, is a very complicated, labyrinthine thing, fraught with terror, hope, joy and sorrow. And so, too, poetry. To me, the literary voice of the refugee, of the survivor, takes many forms, but the one that demands the most attention in any community is almost always that of the poets.

Line per line, inch per inch, more of the human soul is compressed into those words than any other literary form. You don’t get the pages and pages of a whole novel to get your experience across. Not even a whole short story. A poem is ultimately, a very brief but powerful expression, a voice against the silence, a flickering light upon the secrets of the world. And there are many.

As refugees, in the process of rebuilding and trying to begin your life all over, often the jobs you take, the lives you lead give you very little time to mull over the proper construction of plot, rising action, falling action, or whether or not you’re using an imperfect narrator in the second person correctly. You get to write poetry between shifts. On breaks. Perhaps sneaked in during a commute or waiting for a shipment to come in.

Poetry at its best is a deeply democratic form that refugees at any post-conflict social strata can engage with as both a listener and a contributor. For many, though, our engagement with English was only for the practical, not the imaginative. Learn only the English that helps you get a job or finish school.

The language that lets you tell other about your journey is a luxury.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. For those of you I’m meeting for the first time tonight, it may be helpful to discuss my background.

I was born in the closing years of the Laotian Civil War, which took place following the end of French Indochina in 1954. Although Laos established its independence and was recognized by the United Nations, there was still deep uncertainty about how we might conduct our affairs as a people. Although we were officially a neutral nation according to the Geneva Accords, in fact, this led to a secret war between the US-backed Royal Lao Government and the communist Pathet Lao backed by North Vietnam and the Soviet Union.

During the war, the Central Intelligence Agency raised its largest secret army in the history of the agency and the second largest city in all of Laos became the secret airfield of Long Cheng where combat operations were organized to stop communist forces from taking over Laos, but also to prevent the use of the Ho Chi Minh trail that was secretly delivering troops, ammunition and supplies from North Vietnam to fight in South Vietnam. By the time the Secret War ends, more tons of bombs will have been dropped on Laos than on all of Europe during World War 2. Chemical agents such as Agent Orange will cause devastating environmental damage that continues to this day, all in an effort to eliminate foliage hiding enemy troops.

But few in the US knew that story. Few know the story of the Hmong who were assigned to rescue downed US airmen trapped behind enemy lines, often at a cost of 10 lives to 1 according to some estimates. When our communities began to arrive we were called invaders, a yellow horde, refugees who needed to go back where we came from, even though it was US policy that helped create the conditions that necessitated us leaving everything behind in the first place.

40 years later, watching the contemporary refugee and immigration crisis, there are many people who take our position for granted. I won’t remark on that now, other than to say I think it’s a poor thing for anyone to forget their roots.

Today in the US there are over 260,000 Lao, with over 12,000 in Sacramento county. California has over 60,000 Lao making it the largest state for Lao refugees. This county has the largest population of Lao in the US, but do you see that reflected or honored? Do you see resources committed to assisting Lao refugees reasonably?

At the moment, fewer than 1 in 10 Lao will graduate college, yet this story is unheard, and we have few advocates for the Lao community in the public eye. After 40 years here, we have less than 40 books in our own words on our own terms. And I’ve written six of them.

That being said, it’s taken me forty years to really grasp all of this, its scope, its scale, its meaning for us all. And I know there’s still much to learn. But I can tell you, growing up there were nearly no books on Laos, or our modern conflict. It’s a strange thing for many of us who have now spent more of our lives living outside of our birthplace than in it. For my generation and those before me to grow up to be strangers to our own homeland.

Trying to understand your history becomes even more difficult when much of the details of the Secret War were classified, marked secret, with records destroyed and testimonies denied. In our conflict in particular, poetry became helpful for me, and for many others, to describe our experiences, our inner lives, our emotions and so on, in a nonlinear fashion.

It’s been very difficult for many of us to write our tales because it’s difficult to fill in so many gaps we didn’t experience, or that we weren’t told. Often, the accounts we have on record so far are presented from a very biased viewpoint that always privileges the colonizing forces or the US perspective.

Frankly, growing up, much of my time incuded watching the movies such as Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, or even Bridge on the River Kwai where Asians are presented as faceless hordes or downtrodden villagers with no agency or “me so horny” prostitutes hungry for American dollars. On the other hand, the more I discovered my heritage and history, the easier it became to relate to my experiences through the lens of science fiction, of fantasy, and even horror.

In comic books in the 1980s and 90s, there’s a character known as Wolverine who was part of the Weapon X program to create a perfect super soldier, who had his memory tampered with so many times he had no idea who he really was. For me, that was as apt a metaphor for what it’s like trying to find your past if you came from Laos.

I could relate to the themes of Blade Runner more than the Asians of the Joy Luck Club, let alone the ladies of Steel Magnolias. Asking: “Who am I? Why am I here? How long have I got?” Often, science fiction has been able to express the emotional and even spiritual sense of what it is to encounter “the Other,” and what it means to resolve a conflict between cultures, and a question of identity.

This isn’t to say there aren’t some shared experiences that are universal, but it would be a gross mistake to assume that they can be found expressed in much of what has passed for mainstream media and art today.

There’s often that fear that if we criticize the US we’re demonstrating an offensive lack of gratitude. Forty years in, as I talk with the various oral history collection projects, it’s clear there’s a lot of sensitivity about the war and how we’re allowed to tell the story.

In part, that’s where speculative literature can and must come in. To allow us to imagine, and to hold a conversation that considers alternate perspectives, to use symbolic and imaginary or mythic imagery to discuss realities to painful to tell otherwise.

We’re allowed to create a coded world while still addressing the deeper lessons of our journey. We can call back to ours epics such as Phra Lak Phra Lam, the Lao version of the Ramayana and discuss what it means to be a people whose lives are shaped so much by conflict. I know of artists in our community who’ve been able to challenge our past, our history by framing it as ghost stories or as a zombie apocalypse.

And at another level, I think it’s so important for refugees to learn to write and express a future they see themselves a part of.

Although many dismiss it today, I think of Wittgenstein’s classic phrase “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” If you cannot express it, how can you move towards it? Thus, you’ll often find poems of mine that address a future Lao space program, or a science of Laobotics, or something as simple as making the world’s largest padaek factory.

In many parts of the world it’s not possible for people to express themselves freely. There are governments that let you say many things, as long as it doesn’t criticize the government or its officials. I often tell my students that in a democracy, we have a responsibility to write to the very limits of our imagination for the sake of our brothers and sisters who cannot.

I point out that no one can guarantee you’ll be read a hundred years from now, let alone a thousand. You might not be read ten years from now, or ten days. But if you don’t write there will be nothing to be found.

They say that what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger. I look back on my path and realize what keeps us silent makes us weaker.

There is, of course, always an imperative to assemble memoirs, oral histories and children’s books in a community. But time and time again, refugee communities like my own found ourselves faced with the challenge that we aren’t present in the US at numbers to be “marketable” or “commercially viable” to mainstream presses or even smaller publishing houses.

The advice is typically horrible, especially in MFA workshop classes that have often left poets and emerging writers so riddled with self-doubt that they’re barely finishing manuscripts let alone texts that aren’t compromised to serve a mainstream narrative.

We’re encouraged to provide stories in which the US characters are always the heroes such as the Clint Eastwood film Gran Torino or the Mel Gibson film Air America. And there are certainly stories such as this, of deep friendships against the odds. But a mature community deserves and can handle diverse stories, diverse accounts. Or else their literature suffers and they become permanently locked into a narrative that you don’t exist unless you discuss your war or your family’s flight.

The inner lives and imagination are lost, and I think that’s a very toxic scenario for a refugee community. You don’t see every American novel include a response to the war of 1812, or a reflection on John Wayne and what World War 2 means to me. We get past that. But how does a refugee community rebuilding itself get to that point? I wish there was a perfect answer, but through poetry and a persistence to write, I think we come closer.

And I see we’ve run out of time for tonight. But thank you, and I hope this is helpful.

Preface: As a poet and a long-time presenter on various subjects involving Southeast Asian refugee literature in diaspora, I prefer my talks with my students to be conversational and organic rather than firm and fixed lectures.

Memory is a very funny thing, and I found recording what I talk about loses much of what I try to convey. I think poetry is best discussed in a certain 4-dimensional space that a camera from a fixed point or two rarely succeeds in capturing. So, I typically discourage recording for a number of reasons, including the challenge of creating a safe space for open dialogue on what are often sensitive issues. If a poet’s doing their job, then the best will stick and linger with you. Rarely the whole lecture. But something. And that’s an important part of our process.

Still, there are some things I like to consistently touch on. So, for those who couldn’t stay the whole evening, here are the notes I was working from. Those who were there will be able to tell you these were heavily adjusted on the fly to meet many of your questions. These might be helpful to you as you take your own literary journeys.

George Orwell, the author of the dystopian classic 1984 used to say that “A poetry reading is a grisly thing.” And I’ve been to enough in my lifetime that I can see where one might get that impression. A good poet tries not to leave the room with more, newer enemies of literature than when they first walked into it. I think that should be our professional courtesy to each other.

But why poetry? I think poetry is a form that’s mystifying to many people because of the way it is typically introduced to people in the early years. We’re used to forms of literature and language where written things spell everything out precisely and clearly. It’s a very modern American thing to love the simple and the practical and the obvious when it comes to using everyday language.

The physicist Paul Dirac used to joke, semi-seriously that “"In science one tries to tell people, in such a way as to be understood by everyone, something that no one ever knew before. But in poetry, it's the exact opposite." I think about that a lot as I create my own poems, as I think back to the transitions, the journeys that have led me to this path as a poet.

As a Lao American poet, my particular focus is on speculative poetry, a branch of poetics that embraces the fantastic, the imaginative, the mythological, the supernatural and the unreal. It’s an area where I presently seem to have little company, yet it’s a realm of significant and vital importance for refugees in our reconstruction, as I hope to explain throughout the remainder of this conversation tonight.

The Vietnamese poet Mong Lan used to say that all poetry is love poetry, and to a degree I agree with her. But love, true love, is a very complicated, labyrinthine thing, fraught with terror, hope, joy and sorrow. And so, too, poetry. To me, the literary voice of the refugee, of the survivor, takes many forms, but the one that demands the most attention in any community is almost always that of the poets.

Line per line, inch per inch, more of the human soul is compressed into those words than any other literary form. You don’t get the pages and pages of a whole novel to get your experience across. Not even a whole short story. A poem is ultimately, a very brief but powerful expression, a voice against the silence, a flickering light upon the secrets of the world. And there are many.

As refugees, in the process of rebuilding and trying to begin your life all over, often the jobs you take, the lives you lead give you very little time to mull over the proper construction of plot, rising action, falling action, or whether or not you’re using an imperfect narrator in the second person correctly. You get to write poetry between shifts. On breaks. Perhaps sneaked in during a commute or waiting for a shipment to come in.

Poetry at its best is a deeply democratic form that refugees at any post-conflict social strata can engage with as both a listener and a contributor. For many, though, our engagement with English was only for the practical, not the imaginative. Learn only the English that helps you get a job or finish school.

The language that lets you tell other about your journey is a luxury.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. For those of you I’m meeting for the first time tonight, it may be helpful to discuss my background.

I was born in the closing years of the Laotian Civil War, which took place following the end of French Indochina in 1954. Although Laos established its independence and was recognized by the United Nations, there was still deep uncertainty about how we might conduct our affairs as a people. Although we were officially a neutral nation according to the Geneva Accords, in fact, this led to a secret war between the US-backed Royal Lao Government and the communist Pathet Lao backed by North Vietnam and the Soviet Union.

During the war, the Central Intelligence Agency raised its largest secret army in the history of the agency and the second largest city in all of Laos became the secret airfield of Long Cheng where combat operations were organized to stop communist forces from taking over Laos, but also to prevent the use of the Ho Chi Minh trail that was secretly delivering troops, ammunition and supplies from North Vietnam to fight in South Vietnam. By the time the Secret War ends, more tons of bombs will have been dropped on Laos than on all of Europe during World War 2. Chemical agents such as Agent Orange will cause devastating environmental damage that continues to this day, all in an effort to eliminate foliage hiding enemy troops.

But few in the US knew that story. Few know the story of the Hmong who were assigned to rescue downed US airmen trapped behind enemy lines, often at a cost of 10 lives to 1 according to some estimates. When our communities began to arrive we were called invaders, a yellow horde, refugees who needed to go back where we came from, even though it was US policy that helped create the conditions that necessitated us leaving everything behind in the first place.

40 years later, watching the contemporary refugee and immigration crisis, there are many people who take our position for granted. I won’t remark on that now, other than to say I think it’s a poor thing for anyone to forget their roots.

Today in the US there are over 260,000 Lao, with over 12,000 in Sacramento county. California has over 60,000 Lao making it the largest state for Lao refugees. This county has the largest population of Lao in the US, but do you see that reflected or honored? Do you see resources committed to assisting Lao refugees reasonably?

At the moment, fewer than 1 in 10 Lao will graduate college, yet this story is unheard, and we have few advocates for the Lao community in the public eye. After 40 years here, we have less than 40 books in our own words on our own terms. And I’ve written six of them.

That being said, it’s taken me forty years to really grasp all of this, its scope, its scale, its meaning for us all. And I know there’s still much to learn. But I can tell you, growing up there were nearly no books on Laos, or our modern conflict. It’s a strange thing for many of us who have now spent more of our lives living outside of our birthplace than in it. For my generation and those before me to grow up to be strangers to our own homeland.

Trying to understand your history becomes even more difficult when much of the details of the Secret War were classified, marked secret, with records destroyed and testimonies denied. In our conflict in particular, poetry became helpful for me, and for many others, to describe our experiences, our inner lives, our emotions and so on, in a nonlinear fashion.

It’s been very difficult for many of us to write our tales because it’s difficult to fill in so many gaps we didn’t experience, or that we weren’t told. Often, the accounts we have on record so far are presented from a very biased viewpoint that always privileges the colonizing forces or the US perspective.

Frankly, growing up, much of my time incuded watching the movies such as Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, or even Bridge on the River Kwai where Asians are presented as faceless hordes or downtrodden villagers with no agency or “me so horny” prostitutes hungry for American dollars. On the other hand, the more I discovered my heritage and history, the easier it became to relate to my experiences through the lens of science fiction, of fantasy, and even horror.

In comic books in the 1980s and 90s, there’s a character known as Wolverine who was part of the Weapon X program to create a perfect super soldier, who had his memory tampered with so many times he had no idea who he really was. For me, that was as apt a metaphor for what it’s like trying to find your past if you came from Laos.

I could relate to the themes of Blade Runner more than the Asians of the Joy Luck Club, let alone the ladies of Steel Magnolias. Asking: “Who am I? Why am I here? How long have I got?” Often, science fiction has been able to express the emotional and even spiritual sense of what it is to encounter “the Other,” and what it means to resolve a conflict between cultures, and a question of identity.

This isn’t to say there aren’t some shared experiences that are universal, but it would be a gross mistake to assume that they can be found expressed in much of what has passed for mainstream media and art today.

There’s often that fear that if we criticize the US we’re demonstrating an offensive lack of gratitude. Forty years in, as I talk with the various oral history collection projects, it’s clear there’s a lot of sensitivity about the war and how we’re allowed to tell the story.

In part, that’s where speculative literature can and must come in. To allow us to imagine, and to hold a conversation that considers alternate perspectives, to use symbolic and imaginary or mythic imagery to discuss realities to painful to tell otherwise.

We’re allowed to create a coded world while still addressing the deeper lessons of our journey. We can call back to ours epics such as Phra Lak Phra Lam, the Lao version of the Ramayana and discuss what it means to be a people whose lives are shaped so much by conflict. I know of artists in our community who’ve been able to challenge our past, our history by framing it as ghost stories or as a zombie apocalypse.

And at another level, I think it’s so important for refugees to learn to write and express a future they see themselves a part of.

Although many dismiss it today, I think of Wittgenstein’s classic phrase “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” If you cannot express it, how can you move towards it? Thus, you’ll often find poems of mine that address a future Lao space program, or a science of Laobotics, or something as simple as making the world’s largest padaek factory.

In many parts of the world it’s not possible for people to express themselves freely. There are governments that let you say many things, as long as it doesn’t criticize the government or its officials. I often tell my students that in a democracy, we have a responsibility to write to the very limits of our imagination for the sake of our brothers and sisters who cannot.

I point out that no one can guarantee you’ll be read a hundred years from now, let alone a thousand. You might not be read ten years from now, or ten days. But if you don’t write there will be nothing to be found.

They say that what doesn’t kill us makes us stronger. I look back on my path and realize what keeps us silent makes us weaker.

There is, of course, always an imperative to assemble memoirs, oral histories and children’s books in a community. But time and time again, refugee communities like my own found ourselves faced with the challenge that we aren’t present in the US at numbers to be “marketable” or “commercially viable” to mainstream presses or even smaller publishing houses.

The advice is typically horrible, especially in MFA workshop classes that have often left poets and emerging writers so riddled with self-doubt that they’re barely finishing manuscripts let alone texts that aren’t compromised to serve a mainstream narrative.

We’re encouraged to provide stories in which the US characters are always the heroes such as the Clint Eastwood film Gran Torino or the Mel Gibson film Air America. And there are certainly stories such as this, of deep friendships against the odds. But a mature community deserves and can handle diverse stories, diverse accounts. Or else their literature suffers and they become permanently locked into a narrative that you don’t exist unless you discuss your war or your family’s flight.

The inner lives and imagination are lost, and I think that’s a very toxic scenario for a refugee community. You don’t see every American novel include a response to the war of 1812, or a reflection on John Wayne and what World War 2 means to me. We get past that. But how does a refugee community rebuilding itself get to that point? I wish there was a perfect answer, but through poetry and a persistence to write, I think we come closer.

And I see we’ve run out of time for tonight. But thank you, and I hope this is helpful.

Poor Anima, Bad Blood, and Pork Rinds. Considering the poetry of Khaty Xiong

"Can poetry be a cleansing act? What can language offer in the face of personal and collective trauma?" That's the question Jane Wong is asking as she examines Hmong American poet Khaty Xiong's debut book of poems, Poor Anima. It's been called a work that "grapples with languages, forgotten histories, and narratives of haunting." She does a full reflection over at Warscapes this month.

Khaty Xiong was recently featured at the Poetry Society of America with her poem "Pork Rinds, Watered Rice." She has a sparse style that I find allows for particularly interesting comparison to the work of Souvankham Thammavongsa or the work of Soul Vang, Mai Der Vang, Andre Yang or Burlee Vang.

Presently, her standard bio is:

Over the years, I've spent a great deal of time trying to encourage Hmong writers across the country to emerge. I will admit my continued concern that there are many regions where it still feels like we're not hearing from them. The Deep South and the East Coast, for example, don't come immediately to mind as a zone where many Hmong poets and writers are known yet. But that might be changing.

From what I've seen of Khaty's work, I find much in common with my own, working at once with many of the classic issues of the Southeast Asian experience in diaspora, but trying not to give in to the conventional language and tropes that the mainstream culture would otherwise impose upon us. I think that resistance is most easily executed in poetry.

In prose and film, economic considerations come into play. Marketability and clarity. Certainly, these things are worthy to a degree in the world of arts and letters. But I would critique there's very little room for experimentation and "flipping the script" because so many editors, financiers, and other stakeholders in the production have their idea about what sells for a community that's tagged with the terms "refugees" and "immigrants." In poetry, the stakes seem lower, and yet, that's where the most innovation that can change the rest of the field tends to emerge, in my experience. Khaty Xiong's work over the last 5 years is clearly demonstrating this principle in action.

I'm delighted to see that she's exploring much of the mythology, the traditions of the supernatural, the legends of the Hmong culture in the past and present in her work in poems such as "Pavor Nocturnus" and "Bad Blood." I would hope that many of my colleagues in speculative poetry would also see that she is contributing some very interesting pieces for consideration.

With two chapbooks and a full-length manuscript completed, I look forward to seeing what's next for her, and I expect we will be hearing much more from her in the future. Be sure to get your copy of Poor Anima and see for yourself.

Khaty Xiong was recently featured at the Poetry Society of America with her poem "Pork Rinds, Watered Rice." She has a sparse style that I find allows for particularly interesting comparison to the work of Souvankham Thammavongsa or the work of Soul Vang, Mai Der Vang, Andre Yang or Burlee Vang.

Presently, her standard bio is:

"Khaty Xiong is a second-generation Hmong American from Fresno, CA. Born to Hmong refugees from Laos, she is the seventh daughter among her 15 brothers and sisters. She received her Master of Fine Arts in Poetry from the University of Montana, and is the author of two poetry chapbooks, Deer Hour (New Michigan Press, 2014) and Elegies (University of Montana, 2013). Elegies was the winning manuscript for the university’s annual Merriam-Frontier Award. Xiong’s work has been featured on The New York Times and Verse Daily. Her debut Poor Anima (Apogee Press, 2015) is the first full-length collection of poetry published by a Hmong American woman in the United States. Currently, she resides in Gahanna, OH."As someone who grew up briefly in Montana, went to college in Ohio, and is now spending a lot of time in the Central Valley of California, I approach her work with great personal interest, and appreciate the commitment she's made to the literary life.

Over the years, I've spent a great deal of time trying to encourage Hmong writers across the country to emerge. I will admit my continued concern that there are many regions where it still feels like we're not hearing from them. The Deep South and the East Coast, for example, don't come immediately to mind as a zone where many Hmong poets and writers are known yet. But that might be changing.

From what I've seen of Khaty's work, I find much in common with my own, working at once with many of the classic issues of the Southeast Asian experience in diaspora, but trying not to give in to the conventional language and tropes that the mainstream culture would otherwise impose upon us. I think that resistance is most easily executed in poetry.

In prose and film, economic considerations come into play. Marketability and clarity. Certainly, these things are worthy to a degree in the world of arts and letters. But I would critique there's very little room for experimentation and "flipping the script" because so many editors, financiers, and other stakeholders in the production have their idea about what sells for a community that's tagged with the terms "refugees" and "immigrants." In poetry, the stakes seem lower, and yet, that's where the most innovation that can change the rest of the field tends to emerge, in my experience. Khaty Xiong's work over the last 5 years is clearly demonstrating this principle in action.

I'm delighted to see that she's exploring much of the mythology, the traditions of the supernatural, the legends of the Hmong culture in the past and present in her work in poems such as "Pavor Nocturnus" and "Bad Blood." I would hope that many of my colleagues in speculative poetry would also see that she is contributing some very interesting pieces for consideration.

With two chapbooks and a full-length manuscript completed, I look forward to seeing what's next for her, and I expect we will be hearing much more from her in the future. Be sure to get your copy of Poor Anima and see for yourself.

Emerging voices: Lao American film-maker Timothy Singratsomboune

I had the privilege of interviewing the emerging film-maker Timothy Singratsomboune for Little Laos on the Prairie this month. We discussed his journey as a biracial, bisexual Lao American filmmaker in Ohio. I'm always interested in voices from Ohio because that's where I first was able to begin my journey to understanding the Lao culture myself after a complicated beginning.

He's been deeply engaged with social justice and the Black Lives Matter movement, and he's using his talents to explore his heritage, our community, and who we can become.

I'm proud to see him taking a bold step forward, and I look forward to meeting him in person at the National Lao American Writers Summit this May. His current project is entitled "All the Way Down," and it will be interesting to see it when it comes out. I expect this will be among the first of many more vital films coming from him in the future.

This will be his very first time meeting so many of us in one space, so this will be a very interesting occasion.

He's been deeply engaged with social justice and the Black Lives Matter movement, and he's using his talents to explore his heritage, our community, and who we can become.

I'm proud to see him taking a bold step forward, and I look forward to meeting him in person at the National Lao American Writers Summit this May. His current project is entitled "All the Way Down," and it will be interesting to see it when it comes out. I expect this will be among the first of many more vital films coming from him in the future.

This will be his very first time meeting so many of us in one space, so this will be a very interesting occasion.

Sunday, March 13, 2016

First Draft: A Lao American Poetry Minor

To date, no one has meaningfully discussed what a minor in Lao American Poetry would look like if it were made available in a U.S. college. While there are a great many critics who suggest that the very idea of such a minor being available is as ludicrous and useless as a major in Lao American Literature, they seem to forget there was a time a Creative Writing major was thought impossible and ridiculous to fund at an American university. And now we have an entire ecosystem of MFA programs and institutions such as AWP.

So, indulge me for a moment while I present a thought exercise that may or may not come to fruition in your lifetime.

“The number of units required for the Lao American Poetry minor is 21 units.

A minimum of 12 upper-division units are required for the minor, and you must earn at least a 2.00 GPA in the minor in order to graduate. Further, you must complete at least 3 units of coursework in residence at the university to fulfill minimum GPA requirements.

Required courses for the Lao American Poetry minor:

Two classes from the following: Introduction to Writing Lao American Nonfiction (LAW 201), Introduction to Lao American Poetry Writing (LAW 209), Introduction to Lao American Fiction Writing (LAW 210). *Note: Both classes must be successfully completed prior to enrollment in concentration courses below.

Select a concentration from the following: Lao American Nonfiction Poetry Writing (LAW 301 and 401), Lao American Speculative Poetry Writing (LAW 304 and 404), Asian American Poetry Writing (LAW 309 and 409). *Note: LAW 401, 404, or 409 must be completed during your final semester at the university.

LAW 280: Introduction to Lao American Literature This class may only be taken upon successful completion of the Lao American composition requirement.

LAW 380: Lao American Literature Analysis This class may only be taken upon successful completion of LAW 280.

LAW Upper-Division Literature Elective

*Note: 400 level courses require successful completion of LAW 380 prior to enrollment.

You may find substantial descriptions of Lao American Poetry courses offered each semester by visiting the Course Description and Registration section of the Lao American Writing Department Website.

You may use a maximum of 3 units of Internship or Independent Study credit toward fulfilling requirements in the Lao American Poetry Minor.

***

Friday, March 11, 2016

10th Annual Lao Educational Conference (ALEC) coming March 29th, 2016 to Sacramento

Where does the time go? In Sacramento the Lao American Advancement Organization is bringing the 10th Annual Lao Education Conference to Sacramento State University to help Lao youth on March 29th.

ALEC holds a special place in my heart because I last had a chance to attend in 2009 as a presenter, the same year I won the National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Literature and released my book, Tanon Sai Jai. Nationally-acclaimed spoken word artist Catzie Vilayphonh of the duo Yellow Rage was also in attendance to present with me, and I wound up reading Oscar-nominated, Emmy-winning director Thavisouk Phrasavath's speech for the youth that day. I often wonder where many of the students have gone since.

It's not often that you get to bring Lao students together in the US, and rarely do they have a chance to meet so many positive role models in a close setting. They have an opportunity to really learn some valuable life skills no matter what field of study they pursue.

Sacramento has the largest concentration of Lao in the country, and I think it's vital for our community across the US to support their efforts if you have the means. It's a community that has gone to great lengths to promote education and success, recognizing the diverse paths we take to get there. There are some very innovative businesses, artists and community builders who can be found in the region. Investing in our youth at the middle school level is particularly encouraging because all too often our community efforts focus on supporting our youth in high school and the first few years of college. This, too, is important. But Sacramento community organizers have particularly understood the importance of engaging our youth in middle school to create lifelong learners.

A big thanks goes to Dr. Khonepheth Lily Liemthongsamout who has gone to great lengths to keep up the momentum for this event and to create a positive environment. It's a free conference for all middle/high school Lao American students in Sacramento City Unified School District or the Twin Rivers Unified School District. For adults, a $30 registration is appreciated but not required.

For more information you can visit: https://www.facebook.com/LAAO.org

Reality Adjustment, Alien Sex, Black Forests and F.J. Bergmann

F.J. Bergmann wears many hats in the world of poetry. I first became familiar with her work in the mid-2000s, and I read with her for the very first time at CONvergence in Minnesota in July, 2015, where she gave a very lively and assured performance. Over the years, I have come to appreciate her sense of humor, how seriously she approaches her poems as well as those of others, and her commitment to building a sense of literary community. Based in Wisconsin, she enjoys giving talks and presentations on poetry, as well as performing.

An award-winning poet, science-fiction writer, artist, and web designer, she maintains madpoetry.org, a public-service poetry site for Madison, WI. She is heavily involved with the Science Fiction Poetry Association in multiple roles including the editor of Star*Line, the journal of the SFPA. Additionally, she is the poetry editor of Mobius: The Journal of Social Change.

Her recent accolades include the 2015 Science Fiction Poetry Association's Rhysling Award for the Long Poem, the WFOP 65th Anniversary Poetry Contest, the 2013 SFPA Elgin Chapbook Award, the 2012 Rannu Fund for Speculative Literature Award for Poetry, Heartland Review’s 2011 Joy Bale Boone Poetry Prize, and both the Theme and Poet’s Choice divisions of the 2010 WFOP Triad competition. She has also received an International Publication Prize in the 2010 Atlanta Review contest, won the 2009 Tapestry of Bronze contest, and won the 2008 SFPA Rhysling Award for the Short Poem.

I think there's a lot to learn from her, and thought it would be a good idea to have a conversation with her to get her perspective on literature and the journeys we've been taking. Be sure to visit her websites at http://fibitz.com/ and her journal at http://fibitz.livejournal.com/

Do you mind telling us when you first developed an interest in poetry? How would you describe your access to poetry growing up?

I remember reading some poetry in my single-digit years--my parents had a large anthology of warhorses, a book of Walt Whitman's poems, that sort of thing. Dr. Seuss and the poems in Alice in Wonderland, of course, as well as The Hunting of the Snark. And fairy tales, which I read avidly, often incorporated poems, frequently as incantatory devices, i.e., magical spells. It says a good deal, I think, that when I got married, the person officiating used the Whitman collection from my childhood as a prop.

Have you always been in Wisconsin? How did your family first react to your interest in poetry?

I lived in Paris, France, for two years of my childhood, but grew up in Wisconsin otherwise. I first wrote a poem in eighth grade, and I don't remember ever soliciting any input from my family, none of whom are poets. My husband, Fred, is an excellent first reader, however.

Which poem of yours do you usually recommend to someone who wants to read your work for the first time?

Well, I variegate in style and content a good deal. These two would be somewhat representative of the desired effects: "Grand Tour" and "Suspended Animation"

Do you prefer coffee or tea?

Black or jasmine tea, with milk, sugar, and, ideally, delectable comestibles in elegant surroundings--and I must refer you to "Tea Ceremony," a poem triggered by being served, after I had requested tea, a styrofoam cup containing lukewarm water, accompanied by a generic teabag, artificial sweetener, artificial creamer, and ersatz lemon flavoring,

If you could have any imaginary being for a pet or companion, what would it be?

Probably a dragon, or any similar rideable flying predator. (I am fond of horses and have spent most of my life working with them professionally, but, as herbivores, they tend to be somewhat timorous.) I am somewhat tempted by the invisible sentient garrote/AI proposed in Zelazny's Amber novels, though.

You've had some exciting successes lately, including the 2015 Rhysling Award for Long Poem. How did “100 Reasons to Have Sex with an Alien” come about? And what might the 101st reason have been?

Well, as the epigraph suggests, 287 More Reasons to Have Sex, by Denise Duhamel and Sandy McIntosh, was the direct inspiration. Duhamel was a speaker at a state poetry conference and read from the (hilariously funny) book, which itself was inspired by an addendum to a research paper on reasons why people have sex. I basically tried to include all the genre tropes and SF cultural-lexicon references I could think of. There are nods to a lot of favorite authors, from Damon Knight to James Tiptree, Jr. As far as the 101st reason ... a Mata Hari-esque seduction in order to steal the secrets of FTL travel, I should think!

When we see you writing poems like "Anomaly" and "Transference," it's very clear you're comfortable working with either short forms or long forms. What's your process like in determining the style you use for a particular topic?

The poem ends when it has accomplished what it set out to do, which in the case of horror is best accomplished by leaving off the dénouement, and not explaining too much; in "Anomaly," a short series of disquieting images and events resulted in the feeling of an inescapable nightmare--and you know you always wake--or wish you could--at that moment of peak terror. In the case of "Transference," I was using a rather long list of filler words from a spam e-mail (I've used spam as a source for many poems), so of course I couldn't end the poem until I'd used up all the words.

You've done several chapbooks over the last few years, from 2003's "Sauce Robert" to "Out of the Black Forest" in 2012 with illustrations by Kelli Hoppmann. What are some of the important things you've learned about putting a collection of your work together? And will we see a full-length manuscript in the future?

My work is much more variable in style now than it used to be, so it's harder to assemble a cohesive manuscript, especially full-length. I've put together a number of other chapbooks, as well as longer books, but have not had luck finding a press yet (and have been remiss in submitting as much as I should--still trying to generate more spare time).

The poems in Out of the Black Forest were all written in a few months, all based on fairy tales. It had already been accepted for publication, and the publisher had been talking about finding an illustrator, when Kelli said, "I'm thinking of doing a series of fairy-tale paintings: do you have any fairy-tale poems?" I'd previously written a poem for Kelli to illustrate, and have subsequently written a number of ekphrastic poems based on her paintings (see http://the-toast.net/2013/12/13/three-poems-2/ and http://www.dansemacabreonline.com/#!fj-bergmann/c1xd5).

I now have two chapbook manuscripts based on Kelli Hoppmann-painting series, another chapbook of dark first-contact poems, a full-length SF manuscript, several other manuscripts that are more surreal, and am rapidly accumulating a book's worth of horror poems.

Wisconsin seems to be conducive for many poets and the writers of the fantastic and the imaginative. Of course, there's any number of theories and ideas why, but what catches your interest about the Wisconsin speculative arts scene?

Oddly, Wisconsin seems always to have been disproportionately represented in literature, especially when it comes to poetry (as evidenced by this quote: "More poetry is said to come from Wisconsin than any other state in the Union." Badger State Banner, 4/10/1885). I'd noticed, for instance, that the annual Atlanta Review poetry contest has a much higher number of Wisconsin poets as winners and finalists over the years than what one would expect from random distribution ( I've entered it 13 times, been published 3 times, and been a finalist 7 other times). A magician friend has theorized that the effect is due to a gigantic crystal of quartz underlying most of the state, whose visible peak constitutes Rib Mountain.

If you could adjust any part of reality without any ironic or unintenteded consequences, what would you start with?

Not allowing any media posts--online, social, or other--or political speeches without thorough fact-checking. That would totally transform the world!

You see a lot of trends come and go in speculative poetry as the editor of Star*Line, but what are some of the untapped frontiers at the moment, or some lines of poetic inquiry you think we're needlessly leaving by the wayside?